Ciena, as well, has generally achieved organic growth by acquiring companies. It dealt with bouts of vertical integration by acquiring TeraXion assets as discussed in February 2016 (thank you Mark Lutkowitz for your reporting).

Ciena also transformed into a Nortel-like company after it acquired the entire Metro Ethernet division from the bankrupt Canadian telecom manufacturer, as discussed in my August 28, 2015 BLOG post.

Does the Moniker ‘Chameleon’ Fit?

Maybe Ciena could be called a chameleon . . . just look at their history.

As executives are changed out, or as remaining executives latch onto the latest fad, Ciena’s technology/product direction changes. Let’s look at the track history:

Ciena’s fear in 1997: The lack of engineering talent. So the long-haul equipment supplier acquired Atlanta-based AstraCom, a telecom company for just over $13 million. As Carl Russo, Cerent’s CEO, once pointed out, engineering job shops don’t bring in high valuations when being acquired. Ciena thus secured trained talent on the cheap.

Ciena’s problem in 1998: The lack of design and installation skill sets to support the telco service providers purchasing its product. Ciena solved this challenge by acquiring Atlanta-area-based (Norcross) Alta Telecom, an engineering, furnishing & installation (EF&I) services company, for just over $52 million. Unlike other upstart startups, such as Cerent, Ciena believed it couldn’t outsource these functions and needed tight control of the people activating its equipment for customers.

Ciena felt compelled to keep up in the distance wars with Nortel Networks, where “my reach is bigger than your reach.” One way for Ciena to do this was to beef up their product’s receiver sensitivity. To wit, the company acquired a developer of optical components, specifically photodetectors, for a swan song. Santa Barbara, California-based Terabit was snatched for $11.5 million in April 1998, just as Cerent was finishing the design of the first metropolitan-based optical transport product to see the light of day in a decade.

Organic Growth Seen as the Only Way to Evolve

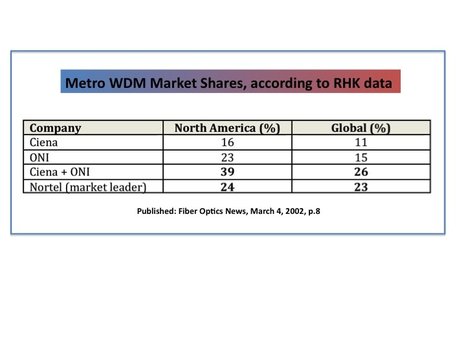

At this point, valuations for small companies began to soar as the larger fish in the telecom business went on a buying spree. Ciena got caught up in this frenzy, but actually made its best acquisition, Lightera, for a relative pittance [1]. This Vinod Khosla-funded startup [2], allowed Ciena to secure a carrier-class optical core switching product and attempt to grow its business by expanding from the long-haul market segment toward the metropolitan market segment, where Cerent was setting up camp. Cupertino, California-based Lightera, gave up its chance to go public by settling for almost half-a-billion dollars in March 1999 and pitting it against formidable cross-connect competitors – Tellabs and Alcatel – opening up new battles for its sales force on two additional fronts. Before this move, Ciena’s competition had primarily been wavelength division multiplexer (WDM) purveyors, Nortel Networks and ONI Systems.

Lightera’s cross-connect, rebranded as Ciena’s CoreDirector, did very well for the company. Flush with this excitement rooted in success, Ciena management reacted to Cerent’s similar market success and cast about for a metro optical transport strategy.

Ciena’s leadership apparently asked three questions.

The first: “Do we build or acquire a multi-service provisioning platform (MSPP) just like the Cerent 454, which Cisco had just paid $6.9 billion to acquire?”

They also wondered: “Or should we get into the metro space with a Metro WDM solution?”

And finally, to crack the large Tier 1 telcos in America, Ciena fretted, “Do we also need an ATM-based technology solution to win that business?”

Ciena didn’t land on one solid answer to pursue. Instead, the company invested in all three approaches and ultimately diluted its efforts.

And last but not least, Ciena invested in an ATM-based production solution, for which the market was declining. This misplaced (and hedging) bet in Acton, Massachusetts-based Wavesmith Networks for less than $200 million occurred in the spring of 2003. Wavesmith’s ATM-based, multi-service edge switch, featuring MPLS capability, failed to inspire a customer base starting its mass migration to IP over SONET, IP over DWDM, or simply an IP + Optical solution offered by companies such as Cisco.

The Chameleon Leveraging Solutions de Jour

I believe Mark Lutkowitz is right, when he tells us, “A principal, overriding theme of our past blog posts focusing on Ciena is that it has not maintained a consistent vision for its future. We believe that historically, it has had a penchant for readily transitioning to the strategies and philosophies of executives, particularly brought on through acquisitions, including from startups that were already on a severe downward trajectory, which had at times resulted in serious financial consequences.”

But Ciena continued to try. It finally recognized the packet (IP) needs of its customers and made two acquisitions with an Ethernet grounding in 2004 and 2008. Internet Photonics [4] and World Wide Packets provided the technology to offer Ethernet aggregation, switching, and transport. This effort was soon superseded by an even more impressive acquisition.

In 2009, Ciena picked up Nortel’s Metro Ethernet division and the company became Nortel 2.0. And that’s where we stand today, even with the departure of Nortel’s Philippe Morin in 2014.

Ciena continues to zig and zag . . . and morph. I wonder what (or who) is next?

[1] On that same day in March 1999, Ciena also acquired Marlborough, Massachusetts-based Omnia for another almost half-a-billion dollars. This carrier-class multi-service access platform did not fair well in the marketplace. It, and its product contributions, are omitted from Ciena’s glossy brochure recounting the history of the company.

[2] Vinod Khosla was not happy with Lightera being acquired by Ciena. His desire was for Cerent to join forces with Lightera to build from the access to the metro and out to the long-haul market. Vinod pleaded with Carl Russo to intervene and talk with Lightera’s CEO, Jagdeep Singh, but there was nothing Carl could do; it was too late. As I wrote in The Upstart Startup, “Carl performed his duty and talked with Jagdeep. But it was clear that he had made up his mind and he was selling out to Ciena and not coming over to Cerent as Vinod had hoped. Speculation demands we ask, ‘Could Jagdeep have done better with Cerent?’” We’ll never know. “Carl remains philosophical, ‘We could’ve put the companies together. Maybe done a lot better, I don’t know.’”

[3]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed